Giant sea spiders, they sound as terrifying as their name and one of their mysteries has finally been uncovered by scientists.

Giant sea spiders in the Antarctic sea sounds like a sequel to a terrible B-tier early 2000 film, doesn't it?

But scientists have not been deterred and continued their research into the species. Odds are you probably haven’t even heard of Antarctic sea spiders, I know I hadn’t.

Advert

But there has been one mystery that has stumped scientists for about 140 years.

The question is how they reproduce.

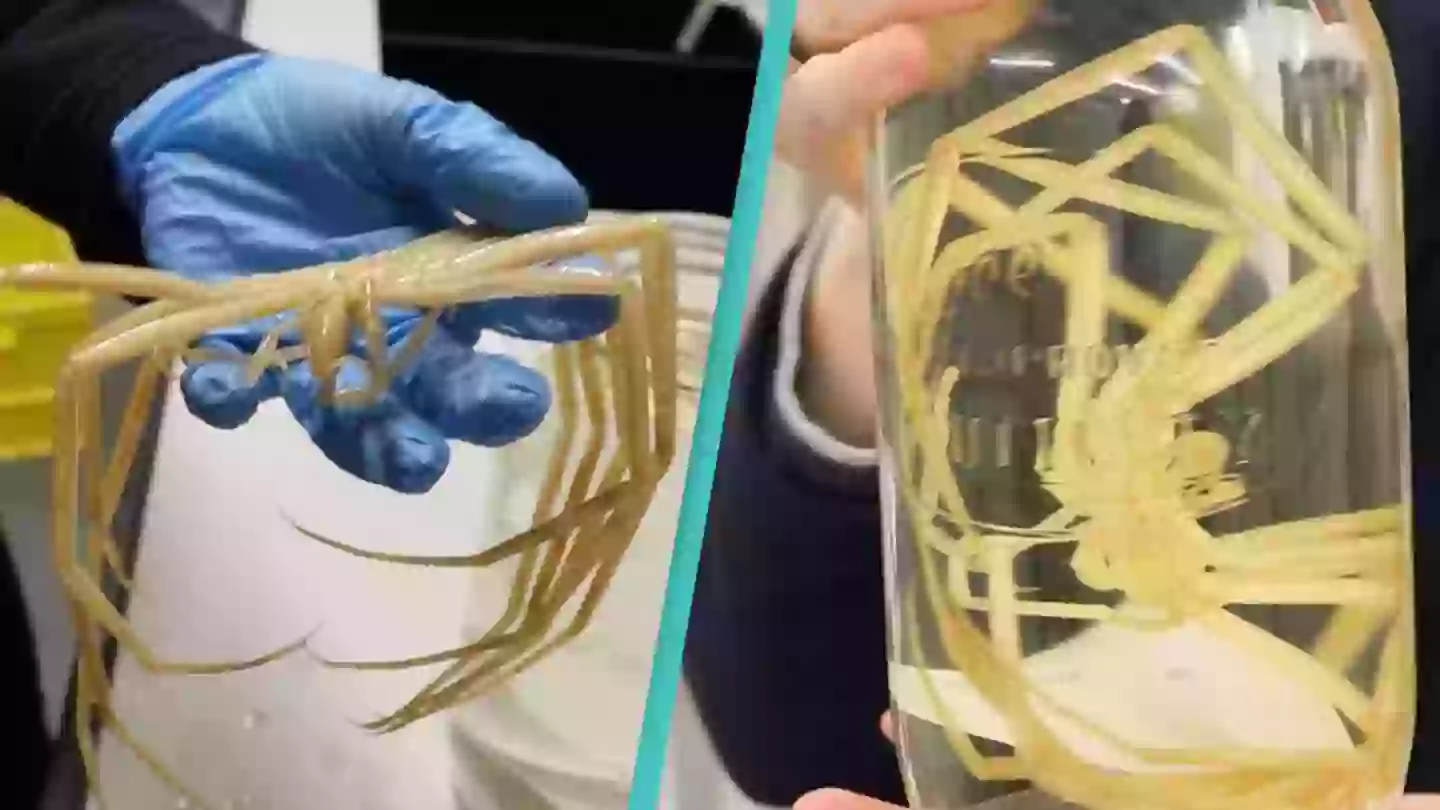

A phenomenon known as ‘polar gigantism’ has resulted in the sea spiders in Antarctica growing to sizes much larger than species across the globe.

Advert

They can even grow up to a foot in diameter, making them fascinating to study.

Their appearance is kind of like an underwater daddy long-legs and the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute has explained how they differ from their land counterparts.

"They’re widespread and occur across a variety of ocean environments. The deep sea is home to the giant sea spider (Colossendeis sp.), which can grow larger than a dinner plate. This spindly spider lumbers along the seafloor on jointed, stilt-like legs,” the institute explains.

“Instead of spinning a delicate web of silk to trap prey, a giant sea spider uses an elongate, tube-like proboscis to slurp up its prey,”

Advert

Researchers at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa recently uncovered secrets about the elusive species and had their findings published in Ecology.

Lead researcher Amy Moran said: "In most sea spiders, the male parent takes care of the babies by carrying them around while they develop.

“What's weird is that despite descriptions and research going back over 140 years, no one had ever seen the giant Antarctic sea spiders brooding their young or knew anything about their development."

Advert

Researchers observed two spiders that appeared to be mating and saw one of the creatures laying thousands of eggs at the bottom of the tanks they were being held in.

One parent then stayed with the eggs for days and attached them to a rocky surface where they stayed before hatching about two months later.

The scientists weren’t exactly surprised this mating and egg laying wasn’t noticed before as they are difficult to see and often covered with algae.

School of Life Sciences Ph.D. student Aaron Toh, who was part of the discovery team, commented: “We were so lucky to be able to see this. The opportunity to work directly with these amazing animals in Antarctica meant we could learn things no one had ever even guessed."