01 Mar 2026

27 Feb 2026

Punch is regularly seen curled up with his plushie, but does he actually feel as heartbroken as the rest of us?

23 Feb 2026

"I can relax and know they're safe"

21 Feb 2026

The study examined how the octopuses' behaviour changed when they were given the drug

The cause sounds like something out of The Last of Us.

09 Feb 2026

Orcas have a sophisticated language to communicate, with different populations even speaking in 'dialects'

23 Dec 2025

Teddy bears are a popular present at Christmas time

17 Dec 2025

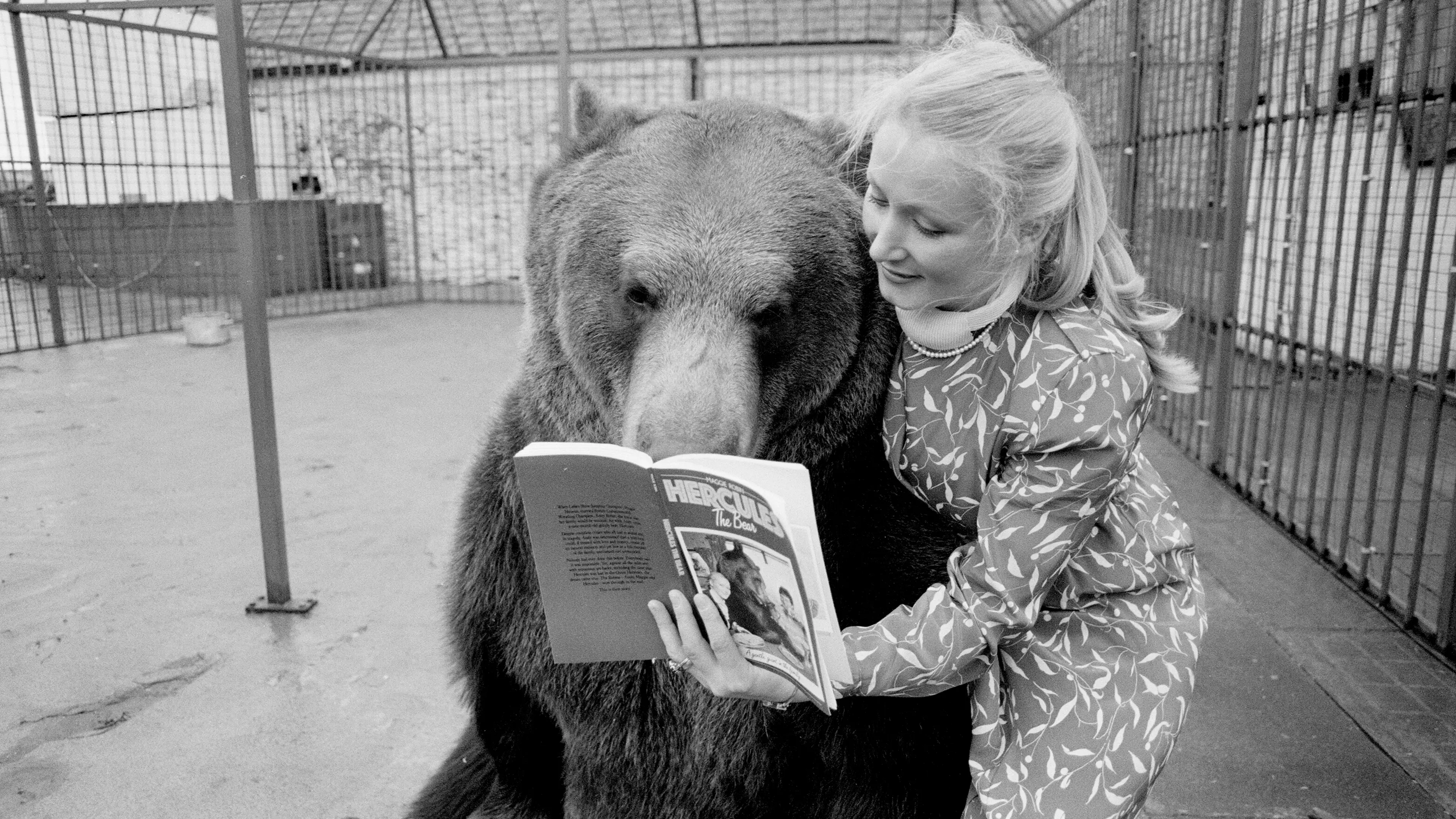

Hercules the bear was quite the star in the 1980s

13 Dec 2025

Smoking weed around your dog could have a serious impact on their health, and even cause life-threatening seizures

Fat cats and chunky kittens might be a thing of the past as a revolutionary new weight-loss drug for pets enters its trial phase

08 Dec 2025

There was one thing about the fossil which left scientists astonished

28 Nov 2025

The vet has explained all after a viral simulation broke the internet

24 Nov 2025

Susan Denker says she would have died if it wasn't for her pooch Lily

23 Nov 2025

Have you ever wondered how cats see the world?

19 Nov 2025

Don't tell me you haven't wondered what your beloved pooch sees when they look at you, other than 'treat dispenser'

16 Nov 2025

The technology may be there, but there are still some other things to think about

03 Nov 2025

Bart Pieciul had been snowboarding when he was attacked by the brown bear

31 Oct 2025

Chimpanzees just proved they might think more like us than we imagined

30 Oct 2025

The beautiful beast was captured sitting in the sun before appearing to look directly at the camera

Almost 40 years on since the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, the radioactive exclusion zone has hit headlines with sightings of blue dogs

29 Oct 2025

Tulane University has reassured members of the public after the monkeys were described as a 'threat to humans'

05 Oct 2025

Dog owner David assured he wasn't going to get rid of the puppy after the incident

24 Sept 2025

Jace Tunnell explained that the 'pink meanies' are not the kind of jellyfish you'd want to eat... despite their candyfloss-like appearance

19 Sept 2025

Annabelle Carlson said her hands 'were pretty mangled'