Astronomers have found new evidence for life on Venus, building on previous research from three years ago.

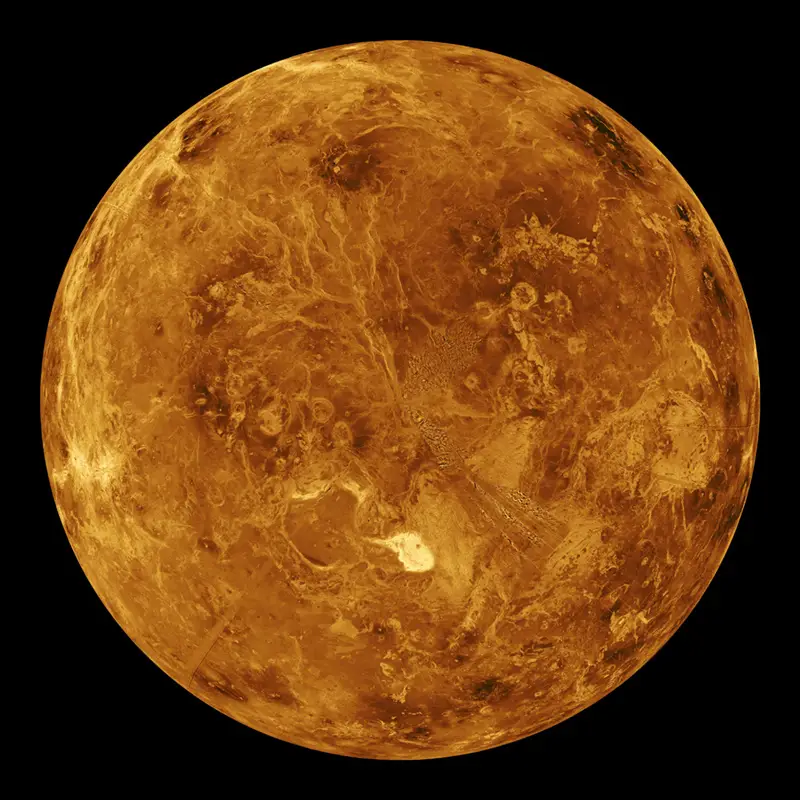

Venus is the second planet from the Sun and Earth’s closest planetary neighbor, which, according to NASA, has a ‘thick, toxic atmosphere filled with carbon dioxide’ and is ‘perpetually shrouded in thick, yellowish clouds of sulfuric acid that trap heat, causing a runaway greenhouse effect’.

The rust-colored planet is also the hottest in our solar system, even though Mercury is closer to the Sun, with surface temperatures on Venus sitting at about 900°F (482°C), which is hot enough to melt lead.

Advert

It also has ‘crushing air pressure’ at its surface - more than 90 times that of Earth, to be precise, meaning it’s similar to the pressure you’d encounter a mile below the ocean on Earth.

Sounds delightful, doesn’t it? Stinky, hot and highly pressurized.

Back in 2020, a team of scientists led by Jane Greaves from Cardiff University in Wales announced they had detected a chemical gas known as phosphine in Venus’ atmosphere.

The phosphine, which is a possible indicator of life, was discovered in the clouds of the planet.

Amid a surge of debate about signs of life on Venus, a number of follow-up studies were conducted but produced little confirmation - until now, that is.

At the Royal Astronomical Society's National Astronomy Meeting 2023 in Cardiff this week, Greaves said phosphine has been found deeper within the planet’s atmosphere than before.

Greaves - who is an astrobiologist at the School of Physics and Astronomy at Cardiff University - and her team had observed the atmosphere of Venus using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) at the Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii, which helped them glance to the top and middle of its clouds.

"There’s a big school of thought that you can make phosphine by lobbing phosphorus-bearing rocks up into the high atmosphere and kind of eroding them with water and acid and stuff and getting phosphine gas," Greaves said as she announced the findings.

The team’s initial findings three years ago proved surprisingly controversial as later research failed to reveal the molecule.

Last year, Martin Cordiner, a researcher in astrochemistry and planetary science at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, explained: “Phosphine is a relatively simple chemical compound - it’s just a phosphorus atom with three hydrogens - so you would think that would be fairly easy to produce. But on Venus, it’s not obvious how it could be made.”

But now Greaves and her team have dug deeper to provide further new evidence.

Greaves continued: "I vaguely remembered Venus is supposed to have this potential habitat in the high clouds, which is anaerobic, and we eventually got telescope time, so I thought, 'Why don’t we have a very quick look and see if there’s some phosphates in Venus clouds, an analog to things living on the surface of the Earth?'

"Astonishingly, we found it, and all hell broke loose!"