Scientists have shared some new research that debunks a 150-year mystery of why human urine is yellow.

For many a year and generations, we've never really thought twice as to why our urine is yellow - it's just the color we always see as we head to the toilet how many times a day.

However, why urine comes out of the human body as yellow has remained a mystery for 150 years.

Advert

That is until now as researchers from the University of Maryland and the National Institute of Health have been working on a study that has brought us much needed answers.

Their findings were published on Wednesday (3 January) in the journal Nature Microbiology. The team of experts discovered bilirubin (BilR) as the key enzyme that makes urine the color we are all familiar with.

Urine consists of water, electrolytes, and waste that is filtered out by the kidneys.

Originally, scientists identified urobilin as the reason behind the yellow pigmentation in urine in 1868. But for so many years after, what caused the color remained a mystery and very much baffled experts on the subject.

Advert

Brantley Hall, an assistant professor in the University of Maryland’s Department of Cell Biology and Molecular Genetics, told Maryland Today: "It’s remarkable that an everyday biological phenomenon went unexplained for so long, and our team is excited to be able to explain it."

So, let's get into the science behind it.

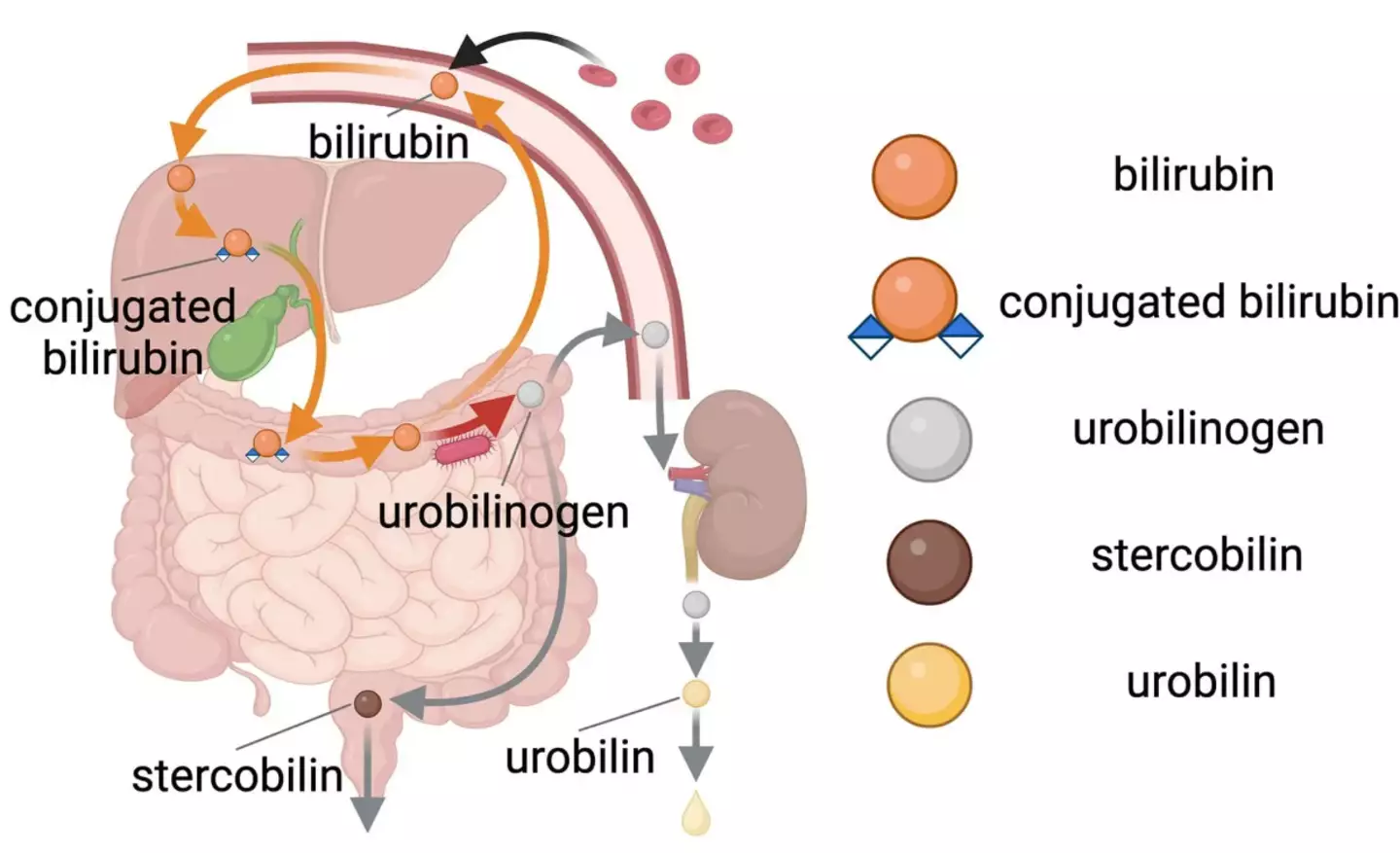

Well, the process happens when red blood cells reach the end of their life cycle at six months, later becoming the bright orange pigment bilirubin.

The pigments then typically seep into the gut, where they are either excreted or partially reabsorbed.

Advert

"Gut microbes encode the enzyme bilirubin reductase that converts bilirubin into a colorless byproduct called urobilinogen,” Hall added.

“Urobilinogen then spontaneously degrades into a molecule called urobilin, which is responsible for the yellow color we are all familiar with.”

The latest discovery is being labelled as a 'remarkable' breakthrough that has solved a critical piece of the 'puzzle' as we try to understand more with the human body.

Advert

Study co-author and NIH Investigator Xiaofang Jiang added to Maryland Today: "Now that we’ve identified this enzyme, we can start investigating how the bacteria in our gut impact circulating bilirubin levels and related health conditions like jaundice.

"This discovery lays the foundation for understanding the gut-liver axis."

Meanwhile, Hall added: "We’re definitely standing on the shoulders of giants. If some of these older scientists had the technology we had today, they probably would’ve found it."