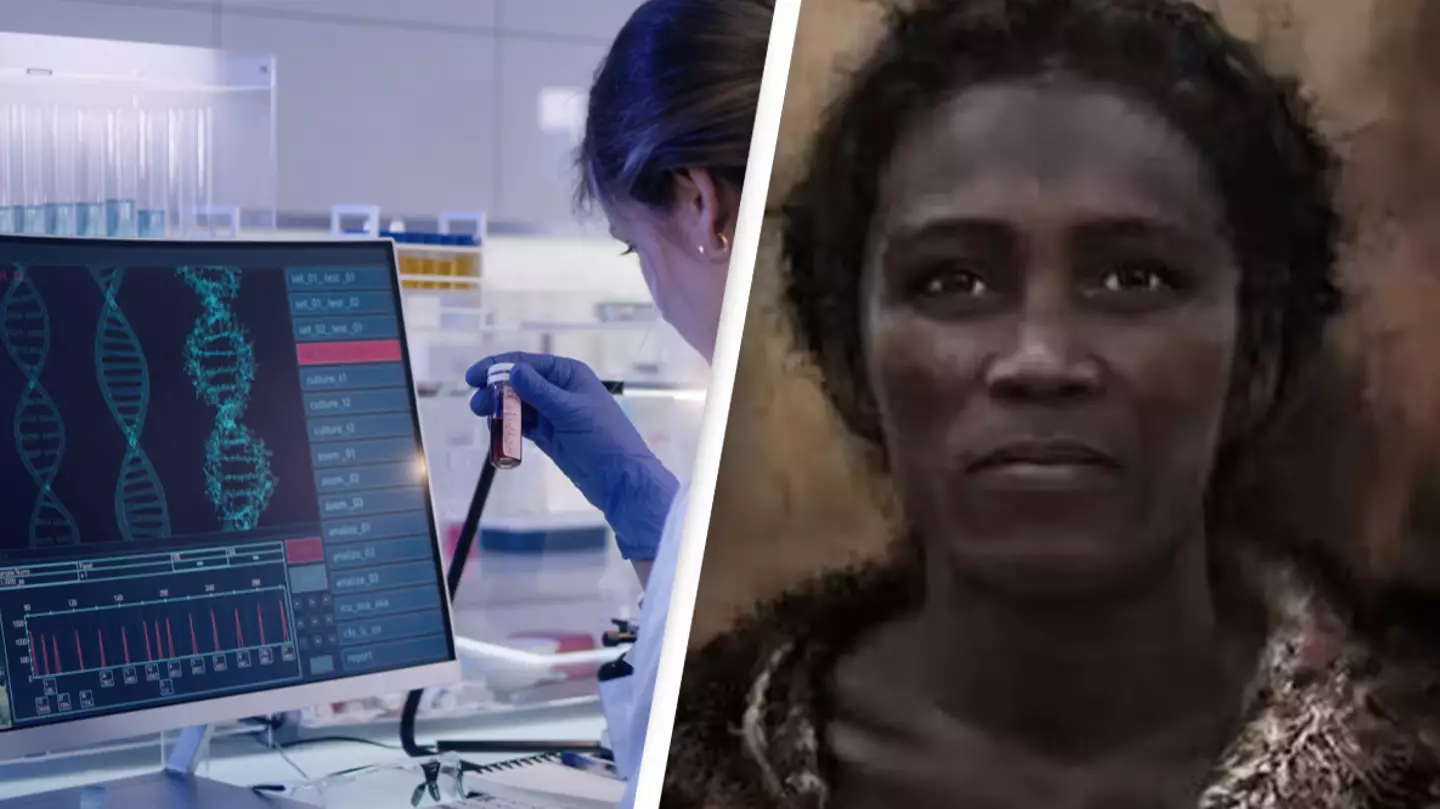

A revolutionary study has found ancient DNA that could just solve the mystery of an extinct lost race.

The study has lifted the lid on the role our Neanderthal cousins played in life as we see it today, and the findings may just see the history of modern humans having to be rewritten.

The ancient human group made Europe their home more than 45,000 years ago, with the research revealing these humans were very much in few numbers - perhaps as low as 200, according to those involved with the study.

Experts looked at remains from Germany's Ranis region, which detailed some close family bonds including a mother-daughter combo.

Advert

According to the BBC, it shows that humans and Neanderthals interbred, offering protection from some diseases, and other humans that didn't interbreed with Neanderthals died out.

Professor Johannes Krause, from Max Planck Institute of Evolutionary Biology in Germany and senior author of the study, told the BBC: "We see modern humans as a big story of success, coming out of Africa 60,000 years ago and expanding into all ecosystems to become the most successful mammal on the planet.

"But early on we were not, we went extinct multiple times."

These humans vanished from Europe around 40,000 years ago, which coincides with the Campanian Ignimbrite eruption, a disastrous volcanic event that likely wiped out humans and animals.

"This is the oldest genome of modern humans, and it represents a lineage that no longer exists," Prof Krause added.

"We believe all human groups in Europe at the time - including Neanderthals - went extinct, and none contributed to the genetic makeup of people alive today.

"This genetic 'package' possibly explains why our species became so successful, ultimately growing to a global population of eight billion."

After this catastrophic extinction event, the researchers believe Europe was repopulated after the ancestors of humans who had travelled further afield returned.

Prof Krause added to the BBC: "Both humans and Neanderthals go extinct in Europe at this time. If we as a successful species died out in the region then it is not a big surprise that Neanderthals, who had an even smaller population went extinct."

Meanwhile, Professor Chris Stringer from the Natural History Museum in London, offered an independent view on the findings.

He said the study shows 'Neanderthals were very low in numbers' during their final days on our planet, and 'less genetically diverse' than their fellow human counterparts they lived alongside on Earth.