If you had to name the largest waterfall in the world, what would your first guess be?

Going by volume of water passing over it, you might think that it's Niagara Falls. With an enormous 3,160 tons of water passing over it every single second, that's certainly a big candidate.

You would be wrong.

Advert

Well, what about by height? Angel Falls in Venezuela would be a good guess, as it stands at a huge 979 metres tall.

Wrong again, I'm afraid.

The largest example we know of a waterfall is an absolute behemoth which makes both of these look like a dripping tap.

In volume, it sends 5 million cubic metres, or around 2,000 times Niagara Falls for comparison. Not even close.

What about in height though?

Well, it's not quite as big a difference, but it's still no contest, with the largest waterfall sending water plunging some 3.5 kilometers, or 2.2 miles.

So where is this enormous waterfall?

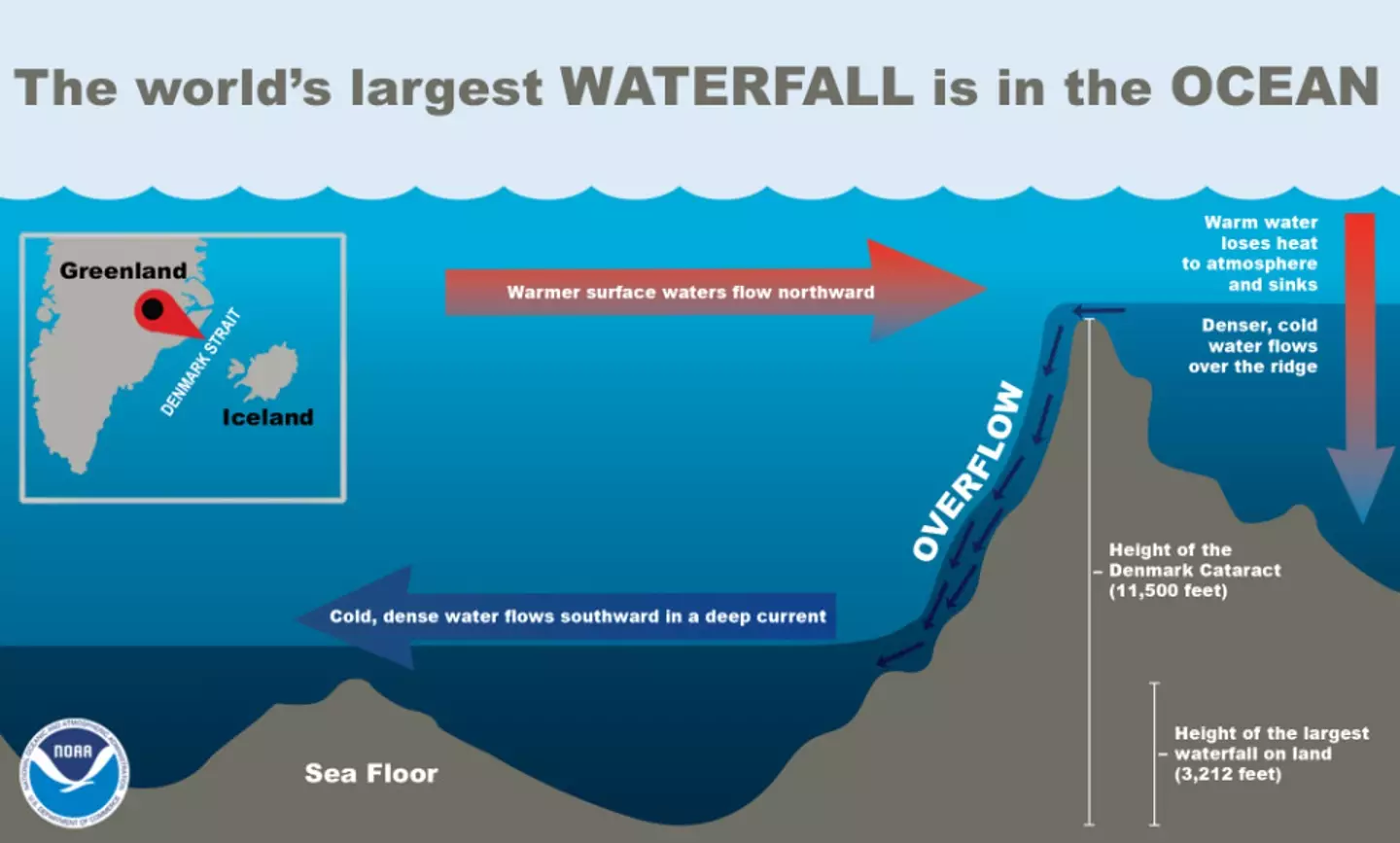

It's actually called the Denmark Strait cataract in the Denmark Strait between Greenland and Iceland, under the surface of the ocean.

But how is an underwater waterfall even possible?

The answer lies in water temperature. While the ocean may appear featureless to the untrained eye, it's actually a whole network of currents and streams which criss cross across the earth.

And of course, the ocean is not confined to the surface, and neither are the currents.

Put simply, colder water will move underneath warmer water. In this case, it's where the colder water from the Nordic Seas meets warmer water from the Irminger Sea, and is pushed underneath it as the two bodies of water meet.

This could create an extraordinary marine environment where nutrients and chemicals are moved between the surface waters and the depths by the ocean currents.

Professor Anna Sanchez-Vidal is leading an expedition to investigate the Denmark Straight Cataract, and explained that cataracts are unfortunately one of the many things in nature impacted by global warming.

As glaciers melt, they result in an influx of fresh water into the oceans, disrupting the currents which move nutrients around and in doing so support marine life.

Prof Sanchez-Vidal said: “A good example is on the Catalan coast, where the decrease in the number of tramontane days in winter in the Gulf of Lion and north of the Catalan coast is causing a weakening of this oceanographic process, which is decisive in regulating the climate and has a great impact on deep ecosystems.”

Topics: News, World News, Nature