It seems that science never ceases to amaze after scientists created were able to create the first 'synthetic embryos', without the use of sperm, eggs or fertilisation.

The achievement is being hailed as a ground-making feat, as it could even help to cure diseases like leukaemia due to the ability to create human cells and tissues using different methods.

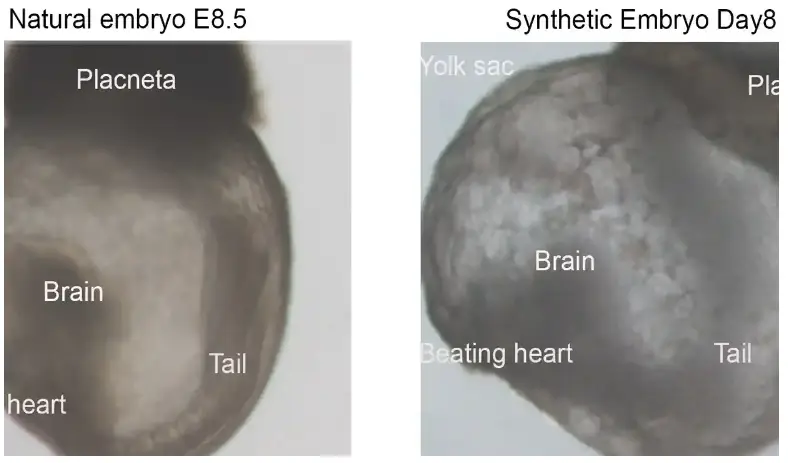

This discovery occurred at the Weizmann Institute in Israel, using stem cells from mice which could make an embryo that has a beating heart, intestinal tract and the early formation of a brain.

Professor Jacob Hanna led these monumental efforts and said in quotes published by the Guardian: “Remarkably, we show that embryonic stem cells generate whole synthetic embryos, meaning this includes the placenta and yolk sac surrounding the embryo.

Advert

We are truly excited about this work and its implications.” The details of the work in full are included on cell.com.

Hanna’s team have taken a leading role in work of this nature, after incredibly managing to construct a mechanical womb which allowed the embryos of mice to grow outside of the uterus for a number of days.

But before we all get carried away too much, Hanna has tempered expectations somewhat by stating that these embryos cannot turn into live animals. This was after these embryos were put into the wombs of female mice.

II would be fair to say that the research is for philanthropic reasons, with Hanna starting a company called Renewal Bio. Their purpose is to grow human synthetic embryos which create tissues and cells for medical conditions.

Talking about the efforts, he said in quotes via the Guardian: “In Israel and many other countries, such as the US and the UK, it is legal and we have ethical approval to do this with human-induced pluripotent stem cells. This is providing an ethical and technical alternative to the use of embryos.”

In light of these huge strides being made, there were some cautionary words from Dr James Briscoe, who is a principal group leader at the Francis Crick Institute in London. He stressed the importance of regulating the research being undertaken into synthetic embryos.

“Synthetic human embryos are not an immediate prospect. We know less about human embryos than mouse embryos and the inefficiency of the mouse synthetic embryos suggests that translating the findings to human requires further development.

“Now is a good time to consider the best legal and ethical framework to regulate research and use of human synthetic embryos and to update the current regulations.”